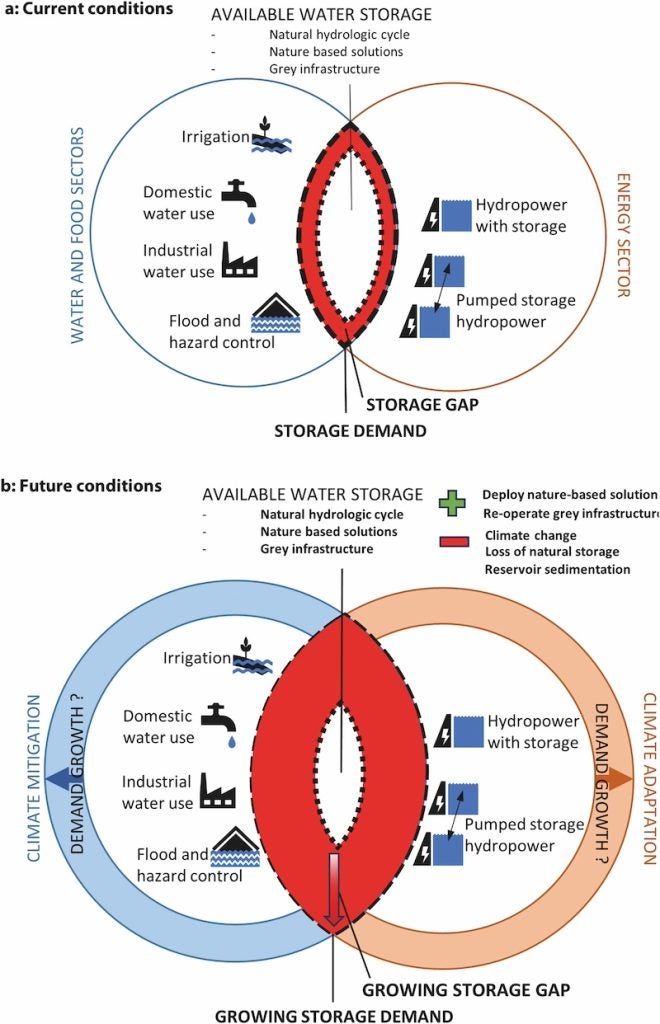

Research by Stanford University and Carnegie Science has been described as a first-of-its-kind global overview of the role dams and reservoirs play in providing water storage. Acknowledging that hydropower and irrigated agriculture are critical for climate mitigation and adaptation, as well as meeting basic human needs in the 21st century, the research team highlighted there was a lack of available data to evaluate the multi-purpose role of existing dams and reservoirs. This is important, the research team observed, as both sectors depend on and compete for the same service, namely water storage.

Rafael Schmitt from Stanford-University and Carnegie Science’s Lorenzo Rosa said that with future demands expected to increase, it’s important to identify crucial gaps in our understanding of what hydropower and irrigated agriculture contribute to food and energy security.

“Water storage is a critical and globally limited resource,” Schmitt said. “Our study shows that the solutions of the past are insufficient, and can be damaging to already overstretched freshwater ecosystems.”

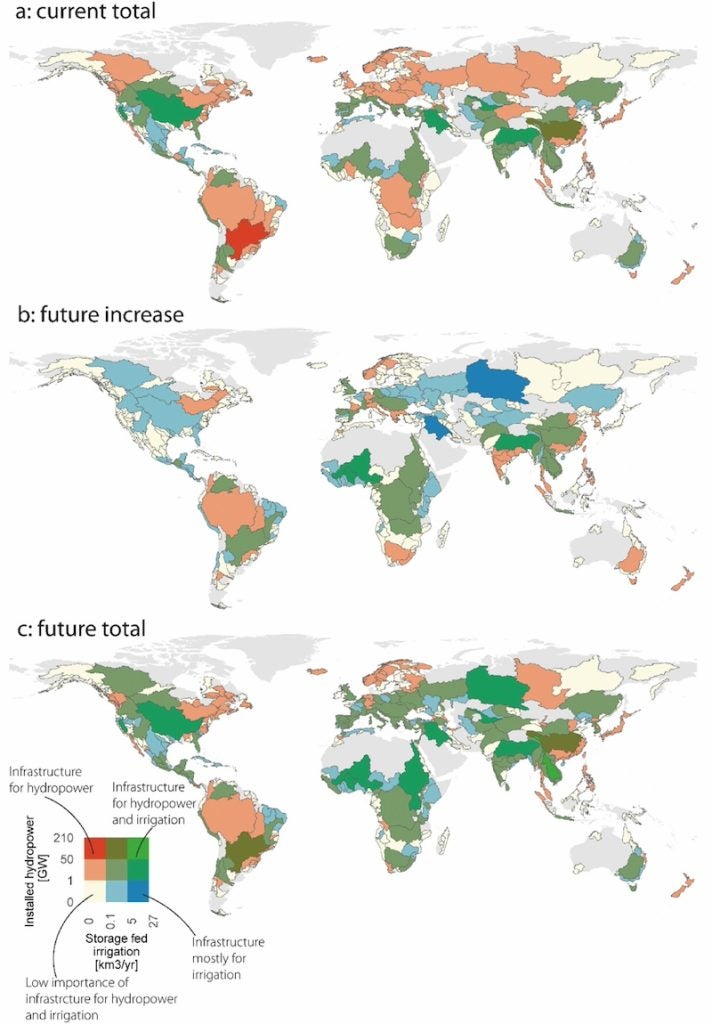

Published in Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, the study used machine learning to quantify the roles of the world’s 6000 largest dams and reservoirs. The analysis revealed that dammed reservoirs globally store about 1000 times the volume of California’s largest man-made lake, Shasta Lake. Of that, less than 5% reaches irrigated crops. With the analysed dams providing 505GW of hydropower, 40% of current total global hydropower capacity, the study projects global demand for hydropower will grow by approximately 35% by 2050, while the global need for stored irrigation water will see a 70% increase.

With over 3700 dams having been identified for potential development worldwide, if all of them were constructed they could provide about 60% more energy and 40% more stored water for irrigation. Despite this potential, the analysis shows that deficits persist in some countries and regions. Even with the construction of several thousand new dams, the authors say there won’t be nearly enough hydropower and stored irrigation water to meet needs in India, central Europe, and several Asia-Pacific nations.

“Our study by no means advocates for building more dams. What we urgently need is a global debate about how to meet water storage needs for critical sectors,” lead author Schmitt commented.

As demands for irrigation and hydropower grow, gaps between sectoral needs and what dams can provide will widen, and the authors warn, the risk for conflicts between these sectors increases as well. Developing a more detailed understanding of emerging operational conflicts between sectors will require consideration of reservoir operations. However it is acknowledged that such regional to global modelling remains challenging and a topic of ongoing research.

“Developing such an understanding and including it into integrated global assessment models and in sectoral studies will be needed to constrain actual gaps for water storage and to identify operational opportunities to close those gaps,” Schmitt and Rosa state.

Shifting focus towards irrigation

Where hydropower lags behind demand, other renewable energy sources could pick up the power slack and even allow dam operations to shift focus toward irrigation. Conversely, increasing reliance on non-grey infrastructure storage options could make it easier for dam operations to shift toward producing more energy, making it possible to build fewer and smaller hydropower projects. Where both hydropower and stored irrigation water are in short supply, the need for alternatives to dams and reservoirs will be all the more acute, according to the researchers.

The study has been described as being a first step towards a unified perspective on water infrastructure for future renewable energy and agriculture systems, but research gaps still persist and require future research.

To conclude, the authors say their research highlights the need to consider the multi-purpose roles of grey infrastructure in debates around impacts and alternatives to future large dams and reservoirs. In turn, this points to the need to consider potential externalities that future food and renewable energy systems, and thus critical systems for human development and climate action, might have if their dependence on grey infrastructure is not overcome.