The construction of dams within transboundary basins can lead to disagreements and conflicts between riparian states, compromising not only environmental and social sustainability but regional stability and peace, according to new research by Susanne Schmeier from IHE Delft Institute in The Netherlands.

Legal and governance mechanisms have been developed to address such conflict potential around projects and range from international water law principles, to dam-specific provisions in basin treaties, as well as basin management plans and environmental impact assessment approaches.

To assess whether, how, and to what extent such institutionalised governance mechanisms can prevent or mitigate conflict, in her research published in Frontiers in Climate, Schmeier presents an in-depth analysis of the Mekong, Zambezi, and Senegal river basins.

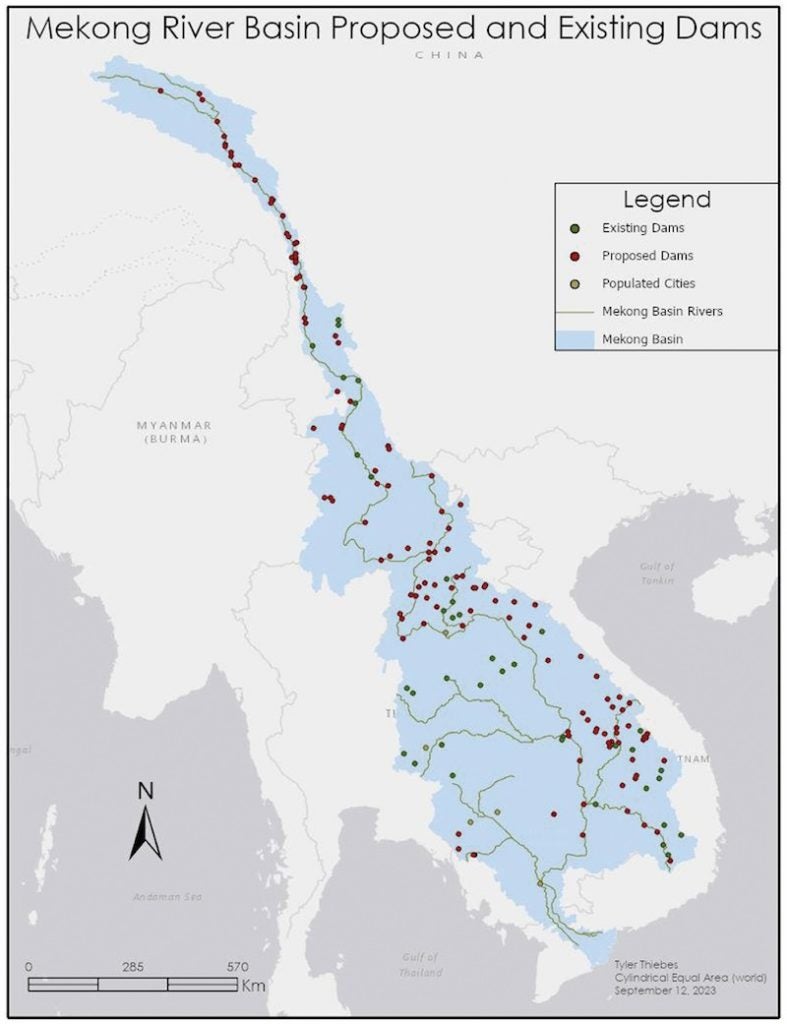

Mekong River Basin

The riparian countries of Lower Mekong Basin have cooperated for decades in an effort to develop and jointly manage the basin’s resources, leading to the establishment of the Mekong River Commission (MRC) in 1995.

As Schmeier states, “there is probably no basin organisation that has conducted as much work on dams as the MRC”, adding that it has developed an unprecedented amount and variety of policies, guidelines and tools. Most significantly, it has adapted to the needs of the basin and developed more targeted and specific mechanisms.

Challenges do however remain, Schmeier cautions, and they illustrate some of the broader challenges with dam development in transboundary basins: “even when a comprehensive set for addressing impacts and related conflict potential exists”.

She goes on to explain that while the conflicts around Mekong dams have been mitigated, riparian people and countries remain vulnerable to dam-induced changes as the environmental and social impacts of the dams have not been addressed sufficiently. And with impacts distributed unevenly across riparian populations and countries, affecting marginalised communities disproportionally, Schmeier warns that this “bears a risk of future conflict”.

Zambezi River Basin

The Zambezi River has a basin shared by eight countries – Angola, Botswana, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe. Zambia and Zimbabwe started cooperation in the 1940s, ultimately progressing towards establishment of the Zambezi River Authority (ZRA) in 1987 and the development of various projects between the two countries.

In 2004, building upon earlier cooperation efforts among most of the basin’s riparian countries, the Zambezi Watercourse Commission (ZAMCOM) was set up with a focus on the integrated and environmentally sustainable management of the entire basin.

Although still a young basin organisation, Schmeier says that ZAMCOM has already made significant contributions to managing the basin in an integrated manner but adds that the Zambezi River Basin “is facing a litmus test in the next years”.

Schmeier explains that as the riparian countries are focused on the economic benefits of existing and new dams, ZAMCOM could play a crucial role in ensuring that dams are being built in effective locations. However, she warns that unless managed in a more sustainable and coordinated manner by ZAMCOM, the dam impacts and their distribution across riparian states are “likely to become a concern”.

The case of the Zambezi River Basin highlights “an interesting constellation” with one basin organisation (the ZRA) dedicated to developing dams for only two of the eight riparian countries, while the other basin organisation (ZAMCOM) aims to manage the entire basin in an integrated manner, trying to prevent and mitigate the potential negative effects of dams and any associated conflicts.

“This divergence in interests,” Schmeier says, “is yet to be reconciled.”

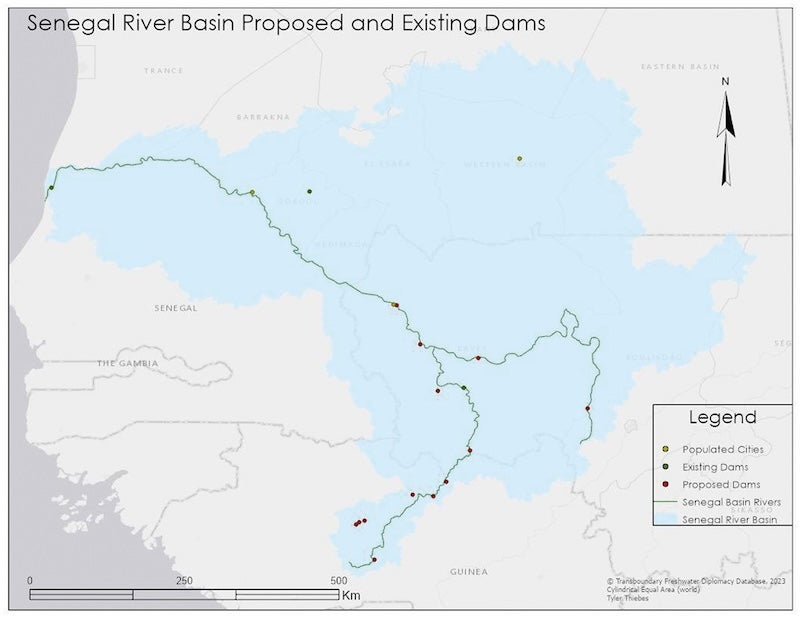

Senegal River Basin

The Senegal River Basin is described as providing “interesting” cooperative insights, having always been focused on the development and management of dams for economic benefits. In 1972 the three lower basin countries, Mali, Mauritania and Senegal, created the Organization pour la Mise en Valeur du Fleuve Sénégal (OMVS), with Guinea, the most upstream state, joining in 2006.

Although the OMVS has been “relatively successful” in building and maintaining commitment to regional cooperation, with a focus on joint water resources development, Schmeier says that the generated benefits have “lagged behind expectations”. These are distributed unevenly across populations, and possibly across the countries too.

“The need to further mitigate environmental and social impacts and engage in more integrated basin management to ensure long-term sustainability might lead upstream states to question institutionalised cooperation even more,” Schmeier adds.

Therefore, she concludes, the OMVS is at a crossroads and will need to continue addressing challenges by developing and implementing additional legal and institutional mechanisms. These must be able to deal with the impacts of dams on the basin’s environment and its people, while balancing interests of riparian states and ensuring long-term commitment to cooperation.

Ongoing dialogue

International water law principles do provide an important framework that can guide states’ behaviour in the development of dams on transboundary rivers, but this also requires basin-specific legal, policy and technical mechanisms that actually implement broader principles and related commitments.

Indeed, the implementation of these mechanisms can also be challenged by design flaws, their implementation, and by the willingness of riparian states to actually put them into action. Even if a comprehensive set of mechanisms for addressing dam impacts and preventing or mitigating dam-related conflicts is in place and indeed implemented, challenges can (re-)emerge.

On-going dialogue through basin organisations is crucial for long-term conflict prevention, Schmeier states. Indeed, the existence of institutionalised cooperation (specifically with regards to dams) “is in itself already an important prerequisite for conflict management as it tends to prevent the escalation of conflicts”.

In conclusion, looking globally, institutionalised cooperation mechanisms are said to be lacking. However in those (albeit rather few) basins where they do exist, they can prevent and mitigate conflict risks. Due to these benefits, Schmeier calls for the promotion and strengthening of such mechanisms to help manage the shared water resources of transboundary river basins.